Kombucha - An Introduction

Ever wondered what kombucha really is? Discover how tea transforms into a probiotic powerhouse!

Kombucha is a deliciously tangy, slightly fizzy fermented tea that has become a staple in wellness circles and kitchens around the world. At its heart, kombucha is created through a symbiotic partnership between beneficial yeast and bacteria, resulting in a unique, probiotic-rich beverage celebrated for its potential gut health benefits. With roots stretching back thousands of years to ancient China, kombucha has traveled along historic trade routes, evolving from an obscure "elixir of immortality" into a popular modern drink available in countless flavor combinations. Whether you're already familiar with fermentation through sourdough baking or you're entirely new to the world of cultured foods, exploring kombucha is a fascinating journey into the transformative power of microbes. Read on to discover what exactly kombucha is, how it’s brewed, and how you can begin crafting your own batches at home.

What is Kombucha?

Kombucha is a fermented tea beverage made by sweetening black or green tea and fermenting it with a live culture of yeast and bacteria. This process produces a tangy, lightly effervescent drink that has a mild vinegar-like sourness and natural carbonation. Often brewed at home, kombucha is typically touted as a healthful probiotic drink, rich in organic acids and B vitamins, though scientific evidence for many health claims is limited. However, research into probiotics and healthy gut bacteria is increasing and as you might know - if you read my recent post on the human digestive system - the large intestine rely on bacteria fermentation to do its job.

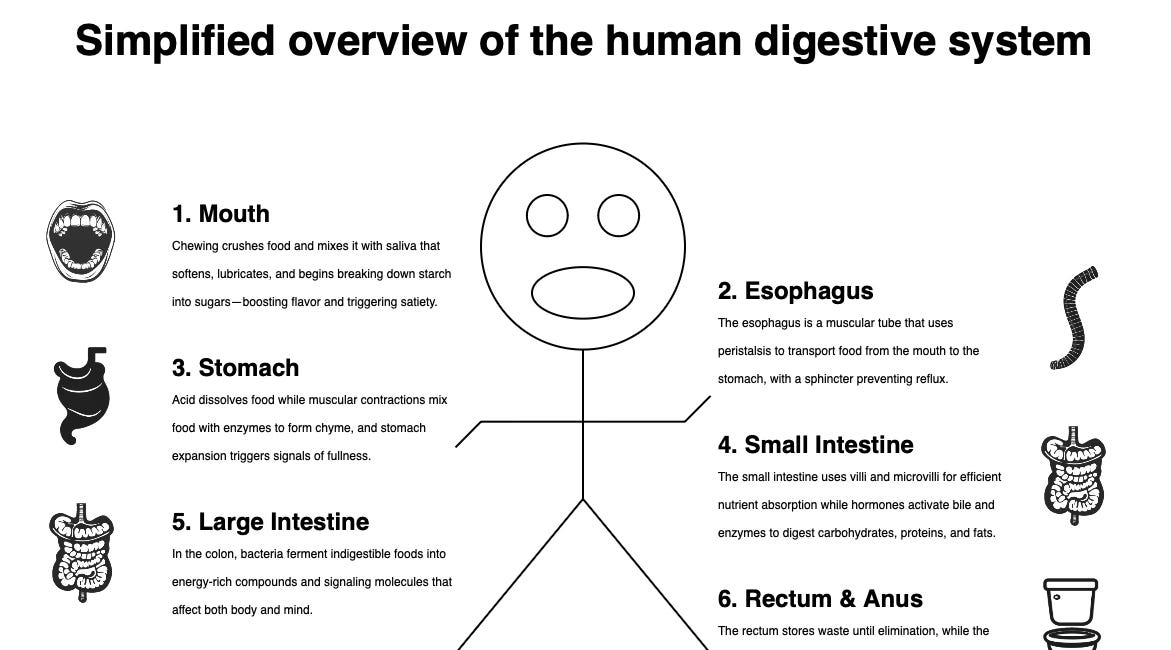

From Bite to Flush - Introduction to the Human Digestive System

Your digestive system is a highly efficient, well-engineered food processing plant that works non-stop to keep you fueled and healthy. Every bite you take goes on an incredible 9-meter journey through this system, transforming raw materials into life-sustaining energy!

What sets kombucha apart is the SCOBY - a floating, jelly-like “pellicle” or mat containing the symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast that drives its fermentation. In fact, the SCOBY (an acronym for Symbiotic Colony Of Bacteria and Yeast) is sometimes nicknamed the “kombucha mushroom” or “mother”, although it’s not a fungus at all, but a living biofilm of friendly microbes.

Kombucha has a long history rooted in traditional fermentations. Its exact origin is uncertain, but most accounts trace it to ancient China. One legend dates kombucha back to 221 B.C. in northeast China during the Qin Dynasty, where it was valued as an elixir for health and longevity.

The most famous legend of Kombucha’s origin dates it to the Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE) during which time … it was referred to as the “Tea of Immortality.” The emperor Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇) is said to have sought to lengthen his life by any means available and this Tea of Immortality was delivered by alchemists at his request.1

From Asia it spread along trade routes - kombucha was brewed in Russia and Eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, often called “tea kvass” or “tea mushroom,” and eventually made its way to Western Europe. In the United States, kombucha first gained modern popularity in the 1990s and then saw an explosion of interest in the early 2000s as part of the natural food and probiotic movement. Today, this once-obscure homebrew can be found in countless flavors on store shelves, even as many enthusiasts continue to brew it at home using passed-down SCOBY cultures much like one might share a sourdough starter.

The Role of Fermentation

Fermentation is the heart of how kombucha is made. In simple terms, fermentation is a metabolic process where microorganisms (yeast and bacteria, in this case) consume sugars and convert them into other compounds like alcohol, acids, and carbon dioxide. When brewing kombucha, you start with a batch of sweet tea – essentially water brewed with tea leaves and sugar. Once the SCOBY and some starter kombucha are added, the mixed microbes get to work. The yeast in the culture feed on the sugar (sucrose) and break it down, producing ethanol (alcohol) and carbon dioxide gas (CO₂) as byproducts. It is the CO₂ that gives kombucha its slight fizz. The bacteria in the SCOBY (primarily acetic acid bacteria) then use the presence of oxygen to metabolize that ethanol, oxidizing it into organic acids. The main acid produced is acetic acid (the same acid found in vinegar), which contributes the sour taste. Smaller amounts of other acids like gluconic and lactic acid are often produced as well, depending on the mix of bacteria. Through this two-step teamwork - yeast first, then bacteria – the brew gradually turns from sweet to tart and acidic. The result after about a week or two is a lightly carbonated, pleasantly sour beverage with only trace amounts of residual sugar and alcohol. Typically, well-fermented kombucha has less than 0.5% alcohol by volume, because most of it gets converted to acids.

This fermentation process is a great example of symbiosis. The yeast and bacteria in the SCOBY coexist and even depend on each other’s byproducts. The yeast make alcohol which the acid-loving bacteria need as fuel; the bacteria make acids and lower the pH, which creates an environment where they (and the acid-tolerant yeast) thrive while inhibiting harmful microbes. In essence, they form a mini-ecosystem that self-regulates the brew’s chemistry. As fermentation progresses, you’ll notice a new layer of SCOBY forming on the surface of the tea - a tangible sign of the microbes growing and doing their work. The rising acidity (pH dropping) protects the kombucha from molds or pathogens, much like how a sourdough starter or yogurt culture becomes safely acidic. By the end of fermentation, kombucha is rich in organic acids (like acetic, gluconic, and lactic), a variety of B vitamins and antioxidants extracted from the tea, and billions of probiotic microbes (if unpasteurized) that remain suspended in the liquid. This symbiotic dance of yeast and bacteria is very similar to other fermented foods. If you’re familiar with making sourdough bread, you may recognize the pattern: yeast and bacteria both contribute to the process, creating a product that’s more than the sum of its parts. In kombucha, as in sourdough, fermentation not only preserves and transforms the base ingredients, but also develops the complex flavors that we love – in this case, converting plain sweet tea into a tangy, effervescent tonic.

The SCOBY Composition and Function

The SCOBY is the defining feature of kombucha fermentation, so understanding it is key. SCOBY stands for Symbiotic Culture of Bacteria and Yeast, which perfectly describes what it is: a living colony of microbes coexisting in a matrix of cellulose.

Physically, a SCOBY looks like a wet, tan-colored pancake or gel disk that floats on the surface of the kombucha. It’s often called the “mother,” similar to how we refer to a vinegar mother - and in fact it behaves in a similar way, acting as the mother culture for each new batch of kombucha.

A SCOBY is not a single organism but a biofilm composed of many species of yeast and bacteria living together. The slimy, cohesive texture comes from bacterial cellulose. This mat is what you hold in your hands as the SCOBY.

Embedded in the cellulose structure are the microbial cells themselves which are a combination of:

strains of yeast

(for example, Saccharomyces cerevisiae)strains of bacteria

(for example, Gluconacetobacter xylinus, also known as Komagataeibacter, which is renowned for its cellulose-forming ability) .

Each SCOBY’s exact microbial makeup can vary, but they always include some alcohol-producing yeasts plus acetic acid bacteria that convert that alcohol to acids .

In essence, the SCOBY is the house where the culture lives: the yeast and bacteria inhabit the cellulose house, and together they ferment the tea.

The SCOBY’s function is both biological and practical. Biologically, it’s the living engine of fermentation – it contains the microorganisms that perform the transformations described above. When you add an active SCOBY to sweet tea (along with some starter liquid), you are essentially inoculating the tea with a ready-made community of fermenters. The SCOBY microbes immediately colonize the new tea, consuming sugars and nutrients and reproducing to form a fresh layer (often called the “baby” SCOBY) on the surface. The formation of a new SCOBY each batch is a byproduct of the bacteria producing more cellulose; you’ll see a translucent film form on the tea’s surface after a few days, which thickens into a new pellicle. This surface growth is no accident – the bacteria need oxygen (they are aerobic) and by residing at the air-tea interface within the SCOBY mat, they get access to oxygen while the liquid below stays mostly anaerobic where the yeast are happier. Practically speaking, the SCOBY acts as a protective barrier and nutrient reservoir. The cellulose mat helps block contaminants (it’s sort of like a raft sealing the liquid below), and it holds many of the bacteria and yeast in place, giving them a competitive advantage over any unwanted airborne spores that might land in the jar. The acidic environment created by the SCOBY’s microbes further defends against mold or harmful bacteria. In a sense, your SCOBY is like a mini eco-system’s coral reef - a structure that hosts and nurtures the community living on it.

Another important aspect of SCOBYs is that they are reusable and self-propagating. After each fermentation cycle, you end up with not only the original “mother” SCOBY but usually a new “daughter” SCOBY layer as well. You can leave them stacked or peel them apart – each is capable of fermenting a new batch of kombucha. This means one SCOBY can give rise to many, and indeed sharing SCOBY “babies” with friends is common in the kombucha world (just as sourdough bakers share starter). As long as it’s kept healthy, a SCOBY can be used indefinitely to brew batch after batch of kombucha . “Healthy” means the culture has food and proper conditions: if you aren’t immediately starting a new batch, the SCOBY should be stored in some fermented kombucha (often called a SCOBY hotel) at room temperature, and “fed” with fresh sweet tea every few weeks to keep the microbes alive and well. With each feed, the SCOBY may grow thicker, and you might periodically trim away older layers. Despite its somewhat alien appearance, a SCOBY is quite resilient when cared for – much like a sourdough starter, it can last for years as an ongoing culture. Just remember the SCOBY itself is alive: it should never be exposed to extremely hot temperatures (which would kill it) or soaps/chemicals. Also, avoid prolonged contact with metal when handling a SCOBY, as acidic kombucha can react with certain metals (food-grade stainless steel is generally okay for brief contact, but it’s best to stick to glass or plastic vessels).

In summary, the SCOBY is the essential fermentation starter for kombucha. It hosts the microbes that transform tea into kombucha, it regenerates itself each batch, and it can be stored and re-used virtually forever. Treat it well - give it the right food and environment - and it will continually reward you with delicious kombucha, much like a well-tended sourdough starter rewards you with endless bread. In fact, making a SCOBY from scratch follows the same principle as creating a sourdough starter - harnessing wild microbes in your environment and giving them a home in your food medium.

Step-by-Step Production Process

Brewing kombucha at home may seem mysterious, but it’s actually a straightforward process. If you’ve baked with sourdough, you’ll recognize the cycle of feeding a culture and waiting for fermentation. Below is a step-by-step guide for making a basic batch of kombucha. Each step includes practical tips to ensure success.

1. Prepare a Clean Brewing Environment:

Sanitize your equipment and wash your hands thoroughly. Kombucha is an open fermentation, so cleanliness is critical to prevent unwanted microbes. Use a clean glass jar for fermenting and avoid metal vessels.

Gather all the ingredients:

water

tea

sugar

SCOBY (along with some kombucha from previous batch or store-bought raw kombucha).

Having everything clean and ready will set you up for a safe fermentation.

2. Brew the Sweet Tea Base:

Brew a strong pot of tea using black or green tea leaves (or a combination). Use 2-3 bags of tea (or equivalent loose tea) in 1 L of hot water. Stick to true tea like black, green, oolong, or white tea. Do not use herbal teas or those with oils (like earl grey with bergamot) as the sole base, as they can lack nutrients or contain compounds that harm the SCOBY.

Add sugar to the hot tea and stir to dissolve - the usual ratio is about 50g of sugar per 1 L of tea, which is a 5% sugar solution. It’s important to use plain cane sugar (white table sugar) for the best results - this is the easiest for the SCOBY to digest.

Once the sugar is fully dissolved, allow the sweet tea to cool down to room temperature (around 20–25 °C). This cooling is vital - never add a SCOBY to hot tea, as heat can kill the yeast and bacteria.

3. Add Starter Liquid and the SCOBY:

Pour your cooled sweet tea into the fermentation jar. If your brew pot is large enough and clean, you can actually ferment in it, but most people transfer to a dedicated jar.

Now add the starter kombucha (kombucha from a previous batch, or a commercially prepared raw kombucha) - usually about 10–20% of the total volume (1-2 dL per 1 L sweet tea). This starter liquid is already acidic and teeming with the right microbes, which helps inoculate the new batch and immediately lower the pH to a safe range.

After the starter, gently slide in your SCOBY on top of the liquid. It may float, sink, or go sideways - any position is okay. Often it will eventually rise to the surface. (If it sinks, a new SCOBY will still form on the top during fermentation.) The SCOBY might be a bit slippery; clean hands or clean latex gloves are recommended when handling it. Once the SCOBY is in, cover the jar with a breathable cloth (like a clean tea towel or paper coffee filter) and secure it with a rubber band. This keeps dust and insects (especially fruit flies) out, while still allowing airflow. Your kombucha is now set to begin fermenting.

4. Ferment at Room Temperature:

Place the jar in a warm, ventilated spot out of direct sunlight. Ideal fermentation temperature is about 20–26 °C. Normal room temperature works fine for kombucha; just avoid areas that are too cold (below 18 °C, fermentation slows down significantly) or excessively hot (29 °C, which can kill or imbalance the culture).

Let the kombucha ferment for about 7–10 days undisturbed. The exact time is flexible - fermentation time can range from about a week to as long as 2 or even 4 weeks, depending on conditions and your taste preference. Warmer temperatures speed it up, cooler temperatures slow it down.

Around day 3 or 4, you’ll likely notice a thin film forming on the surface - this is the new baby SCOBY starting to develop. Also, you may see brown stringy bits dangling from the SCOBY or floating; these are yeast strands, a normal sign of active fermentation. Bubbles may form around the edges of the SCOBY as CO₂ is produced.

Do not stir or shake the jar during primary fermentation - you want that SCOBY undisturbed so it can grow.

5. Check Fermentation Progress:

After about a week, begin tasting your kombucha daily. You can dip a clean straw into the jar (under the SCOBY) and draw out a little, or pour a small sample into a cup.

Taste for sweetness vs. tartness. Early on, it will still taste very sweet (like tea with too much sugar). As days go by, it will get more tart-sour and the sweetness will diminish. It’s up to you to decide when it’s “done” to your liking. A common benchmark is around 7–10 days for a balanced flavor - slightly sweet and nicely tangy. If you prefer a more vinegar-like kombucha, you can let it ferment longer (2+ weeks); it will become more acidic and less sweet over time as more sugar is consumed and converted. Don’t worry about harming the SCOBY by leaving it too long, but do know that very long ferments will eventually yield something close to kombucha vinegar (which can still be used in dressings or as starter for new batches). Once the kombucha reaches a taste you enjoy, it’s time to stop fermentation.

6. Remove the SCOBY and Reserve Starter:

With clean hands, carefully remove the SCOBY from the jar. It may have a baby SCOBY attached to it; you can leave them together as a thicker SCOBY or separate them. Place the SCOBY (or SCOBYs) into a clean bowl or container and ladle some kombucha over it - at least a cup or two. This liquid will serve as the starter for your next batch and keeps the SCOBY wet.

You now have a couple options: you can immediately start a new batch of kombucha using this SCOBY and starter (simply repeat the process by brewing more sweet tea), or you can set the SCOBY aside in a “hotel” – a jar with some kombucha to store it until you’re ready to brew again.

Never let a SCOBY dry out; always keep it in acidic liquid. If not starting a new batch right away, cover the SCOBY’s container and keep it at room temp. Meanwhile, strain or decant your finished kombucha from the fermentation jar into bottles or another vessel, leaving behind any heavy yeast sediment at the bottom.

7. Bottle and Carbonate (Second Fermentation, Optional):

At this point, you have unflavored, “raw” kombucha which can be enjoyed as-is or further carbonated and flavored.

To carbonate, transfer the kombucha into airtight bottles (e.g. flip-top brewing bottles). You may add a bit of extra sugar or fruit juice or pieces of fruit/herbs to provide fresh sugar for a short secondary ferment in the bottle. Seal the bottles and leave them at room temperature for 2 to 4 days. During this time, the residual yeast will ferment the new sugar in the closed container, producing CO₂ which carbonates the liquid (since the gas can’t escape).

After a couple days, the kombucha will be noticeably fizzier. Be cautious with this step: do not leave the bottles at room temp for too long, or use bottles that can’t withstand pressure, because excess CO₂ can build up and cause bottles to burst.

When the carbonation is where you like it, refrigerate the bottles. Chilling will slow fermentation to a crawl, stabilize the carbonation, and of course make the kombucha refreshing to drink.

8. Enjoy and Repeat:

Congratulations - you now have homemade kombucha ready to drink! Serve it chilled, straight from the bottle or over ice. You can strain it if you want to remove any floating yeast bits or tiny SCOBY fragments, but they are harmless to consume.

Each time you make a batch, you’ll produce more SCOBY material; you can keep the extras as backups or share them with friends interested in brewing. For your next batch, use the reserved starter liquid and SCOBY from step 6 and go through the cycle again.

Many brewers keep a continuous rotation, so there’s always kombucha fermenting or carbonating and a SCOBY on standby. With each batch, you’ll get more comfortable with the process - adjusting ferment times to match your flavor preference and experimenting with second-fermentation flavors (common additions include ginger, berries, citrus, herbs, etc.). Just remember to always save some plain kombucha for starter before adding flavors.

Brew safely and have fun with it!

Similarities Between Sourdough and Kombucha Fermentation

If you’re reading this as an avid sourdough baker, you already have a head start on understanding kombucha. If not, the feel free to read my introduction to sourdough and my simply recipe on your first sourdough bread.

Sourdough Basics

Baking with sourdough is the original way of baking—it’s how bread was made long before the invention of isolated commercial baker’s yeast. In fact, baking with sourdough has been practiced for more than 5,000 years!

Sourdough Bread - The Simple Recipe

There is something truly special about baking your own sourdough bread. The process requires patience, but the result—a perfectly crispy crust and soft, flavorful crumb—is more than worth it. If you’ve been curious about baking with sourdough, this step-by-step guide will help you create a delicious loaf from scratch.

On the surface, sourdough bread and kombucha tea seem very different, but their fermentation processes have a lot in common. Both are ancient methods of food fermentation that rely on wild cultures of yeast and bacteria to transform a basic ingredient (flour for sourdough, sweet tea for kombucha) into a flavorful, preserved food or drink.

Let’s explore some of the key similarities.

Symbiotic Microbial Cultures

In both sourdough and kombucha, the fermentative power comes from a community of microorganisms living in harmony.

A sourdough starter is a mixed colony of wild yeast and lactic acid bacteria (LAB) living in a flour-and-water mixture. Kombucha is fermented by yeasts and acetic acid bacteria living together in the tea. In each case, these microbes form a stable symbiotic culture - they balance each other’s growth and even cooperate. For example, in sourdough the LAB tolerate the alcohol produced by yeast, and the yeast tolerate the acids produced by LAB. Similarly, in kombucha yeast and bacteria mutually support the environment (yeast make ethanol for the bacteria to convert to acids, and both thrive in the acidic, low-sugar conditions that result).

In short, both sourdough starter and kombucha SCOBY are SCOBYs in the generic sense – both are Symbiotic Cultures of Bacteria and Yeast, just thriving in different mediums.

Feeding and Maintenance

Maintaining a sourdough starter and a kombucha SCOBY involve very similar care routines. In order to keep the culture alive and active, you must periodically feed it fresh nutrients. Sourdough starter is fed new flour and water (which provides sugars/starches for the microbes) usually every day or week, depending on how often you bake. Kombucha’s SCOBY is “fed” by starting a new batch with fresh sugary tea each cycle, or by adding sweet tea to a SCOBY hotel for storage.

In both cases, if you neglect to feed the culture, it will eventually exhaust its food, the ferment will slow down, and the microbes could die or go dormant. Both can be stored cooler to slow their metabolism (sourdough in the fridge, SCOBY in a jar of kombucha at room temp for a while), but they’ll need to be fed again to become active.

The takeaway: both kombucha and sourdough involve culturing a living colony that you regularly refresh with new food.

Fermentation Byproducts and Flavor

The metabolic outputs of the microbes bear similarities. In sourdough fermentation, yeast ferment sugars from flour to produce carbon dioxide (to leaven the bread) and small amounts of ethanol, while lactic acid bacteria produce lactic acid (and some acetic acid) which give sourdough its tangy flavor. In kombucha, yeast produce CO₂ (for fizz) and ethanol, and bacteria produce acetic acid (and a bit of lactic acid) which give kombucha its tangy flavor. In both cases, the presence of organic acids is a hallmark of fermentation - lactic acid in sourdough, acetic acid in kombucha - making the environment acidic and imparting a sour taste.

The production of carbon dioxide is another commonality. The CO₂ bubbles in kombucha are akin to the CO₂ that gets trapped in bread dough to make it rise. So whether it’s a loaf of rustic bread or a fizzy jar of fermented tea, yeast are generating carbon dioxide and alcohol, and bacteria are producing acids, each contributing to the unique flavor and texture of the final product.

Optimal Conditions

Kombucha brewing and sourdough fermentation thrive under similar environmental conditions. Both prefer a moderate warm temperature – around 21–24 °C is often cited as ideal for sourdough starters, and kombucha similarly does well around 23–25 °C. If it gets too cold, both fermentations dramatically slow: your sourdough might become sluggish and your kombucha SCOBY might go nearly dormant (and as a result, not acidify the tea enough, risking mold).

Both also need some exposure to air (at least not complete airtight seal during primary fermentation). Sourdough starters are usually kept in a loosely covered jar, allowing the culture to breathe and preventing pressure buildup from CO₂. Kombucha is covered with a cloth, providing plenty of airflow for the aerobic bacteria.

Light is not critical for either (they can ferment in the dark; in fact, direct sunlight is discouraged for kombucha as it may degrade components or overheat the jar).

Time is another similarity: both processes require patience - you might feed a sourdough starter for days to get it going, and kombucha takes a week or more to ferment. This slow, ambient fermentation is a common thread in traditional fermenting.

Continuous Culture and Longevity

Both kombucha SCOBYs and sourdough starters are effectively immortal cultures – they can be propagated indefinitely. Sourdough bakers often boast starters that are many years old, passed down through generations. Kombucha brewers can use the lineage of a SCOBY for countless batches. In each case, you save a portion of the live culture to inoculate the next batch. With sourdough, you reserve a piece of the dough or a bit of starter to keep feeding; with kombucha, you reserve the SCOBY and some liquid from the jar to start the next brew.

As one might expect, both cultures tend to evolve over time - environmental microbes might integrate, or certain strains dominate - but as long as they’re kept healthy, they remain effective. This concept of a self-perpetuating fermentation is fundamental to both arts. You might even say a kombucha SCOBY is the “mother dough” of the kombucha world.

The idea of sharing and trading cultures is common to both communities: bakers swap starter cultures; kombucha brewers swap SCOBYs. This highlights another similarity: they are both accessible, DIY fermentations that many people keep at home, contributing to an ever-growing community of practice.

Microbial Benefits and Probiotics

Many people appreciate sourdough and kombucha not just for their taste, but because they’re fermented and probiotic-rich.

A sourdough starter, like kombucha, hosts beneficial bacteria that can have probiotic effects (though baking the bread kills the live microbes, the fermentation byproducts remain). Kombucha is typically consumed raw, delivering those live bacteria and yeasts to the gut. In both cases, the presence of these microbes and their metabolites is associated with improved digestibility of the base ingredients: Sourdough fermentation can break down some gluten and make nutrients more bioavailable in grains; kombucha’s fermentation consumes sugars and produces acids and enzymes.

While the specifics differ, the general principle is the same - fermentation pre-digests foods in ways that can be beneficial. Both sourdough and kombucha enthusiasts often describe their products as healthier alternatives to their non-fermented counterparts (plain bread or sugary soda).

From a culinary perspective, both also add complexity of flavor and aroma that only fermentation can create.

In summary, if you know how to nurture a sourdough starter, you already understand the basics of kombucha care: provide the right food (sugar or flour), keep the culture in a hospitable environment, watch for the signs of active fermentation (bubbles, sour smell), and guard against contamination.

Both fermentations exemplify how beneficial microbes can transform simple ingredients into something sustenance, delicious, and rich in culture – both in the microbial sense and in the human tradition sense.

Basic Troubleshooting and Tips for Beginners

Starting your first batch of kombucha can be exciting but may also raise questions and concerns. Here are some basic troubleshooting tips and best practices for beginners to ensure your kombucha ferment stays healthy - many of these will sound familiar to anyone with sourdough or home-fermenting experience.

Sanitize and Stay Clean

Ensure all jars, utensils, and your hands are clean when brewing. Contamination is the biggest risk in kombucha brewing because you’re dealing with an open ferment. Wash everything in hot soapy water (or sanitize) and rinse well (no soap residue). This simple step prevents most problems.

Use Sufficient Starter Liquid

Always add the recommended amount of starter kombucha (from a previous batch or a store-bought raw kombucha) to your new batch. The starter’s acidity is critical for preventing mold and bad bacteria. A good rule of thumb is at least 10% of the batch volume should be starter. Without enough starter, the sweet tea may stay at a higher pH for too long, inviting mold. If in doubt, you can even use more starter - it won’t harm anything aside from making the initial flavor more sour. Low initial pH (below 4.5) is what keeps the brew safe until the SCOBY produces more acid.

Temperature Matters

Kombucha likes warmth. If your brew is kept in a room that’s too cold (below 18 °C), the fermentation will be sluggish or stall. When the culture is sluggish, it fails to acidify quickly and that’s when mold can take hold. Conversely, very high temperatures can kill the SCOBY or cause off-flavors. Aim for that comfortable room temperature range (20–26 °C). If your home is chilly, consider using a heat mat or brewing inside a cupboard above the fridge (somewhere slightly warmer) – but be careful not to overheat.

Signs your brew is too cold: little to no SCOBY growth after a week, and the tea still tastes very sweet.

Signs it’s too hot: the SCOBY might thicken extremely fast or the brew turns vinegary very quickly (or develops a cooked or off smell). Steady, moderate warmth yields the best results.

Choose the Right Ingredients

Stick to the classic ingredients, especially while you’re learning. Use real tea (black or green) - kombucha needs nutrients like nitrogen, caffeine, and tannins from true tea leaves. Herbal teas or those flavored with oils can weaken the SCOBY over time or introduce antimicrobial compounds. If you want to incorporate herbals (like hibiscus or chamomile), use them in combination with true tea, not as 100% of the tea base.

Use plain white sugar. Alternatives like honey, coconut sugar, or stevia can cause problems (they either add wild microbes or lack the easy-to-digest sucrose that the SCOBY prefers). Once you have a few successful batches, you can experiment, but initially keep it simple to build a strong SCOBY. Also, always use non-chlorinated water (chlorine can inhibit the microbes). If using tap water, it’s best to filter it or boil and cool it first.

Don’t Seal the Primary Fermentation

It’s worth emphasizing - never ferment kombucha in an airtight container for the primary ferment. The SCOBY needs oxygen. Cover with cloth, not a solid lid. If you seal it, pressure will build up and, more importantly, your acetic acid bacteria will not get oxygen and can’t make acetic acid properly. Lack of oxygen could also encourage yeast overgrowth or even different anaerobic bacteria that you don’t want. Save the sealed container for after you bottle.

Monitor and Observe

During fermentation, peek at your brew (visually) each day. You should see a whitish or beige film forming on top (new SCOBY) - that’s good. You might see brown stringy bits dangling - those are yeast colonies, also normal. What you should not see is fuzzy growth or vividly colored spots on the surface of the SCOBY or floating on the liquid. Fuzzy circular spots that are white, green, blue, or black are signs of mold (which looks much like bread mold). Mold is the enemy - if you see it, you’ll need to toss the batch. Unfortunately, there is no saving a moldy kombucha; you have to discard the liquid and the SCOBY, because mold filaments/spores penetrate throughout. Start fresh with a new SCOBY and starter (and sanitize the jar well) if that happens. The good news: if you follow the tips above (enough starter, proper temperature, etc.), mold is quite rare. Sometimes new brewers mistake the thin baby SCOBY formation or yeast clumps for mold - if it’s gelatinous or filmy (not dry) and mostly off-white/tan, it’s likely just SCOBY. When in doubt, give it another day or two - mold will usually spread and turn fuzzy if it’s mold. Kombucha does have a bit of a wild appearance, so don’t be alarmed by strings and blobs that aren’t mold.

Keep Fruit Flies Out

If there are fruit flies in your area, be very careful - they love kombucha. They can crawl in through very tiny gaps. Use a tightly woven cloth cover (or a paper towel or coffee filter) and a strong rubber band. It’s also a good idea to keep your fermenting kombucha jar away from fruit bowls or compost bins where flies congregate. One stray fruit fly can introduce vinegar eels or other unwanted things into your SCOBY (besides just being gross). Good covers and cleanliness are your defense.

Avoid Cross-Contamination

If you’re also fermenting other things (like a sourdough starter, kefir, kimchi, etc.) in the same kitchen, keep some distance between the projects. Airborne yeast or bacteria from one culture can potentially affect another. It’s not common, but, for example, a vigorous sourdough starter nearby might introduce yeasts that outcompete your kombucha yeast, or vice versa. Many fermenters stagger their projects or place them in separate corners to be safe. This isn’t usually a big issue, but it’s a consideration if you run into unexplained problems.

Don’t Refrigerate Your SCOBY

While refrigeration is great for slowing fermentation of finished kombucha, do not store your SCOBY in the fridge. The cold can make the SCOBY go dormant and once it’s that inactive, it can be hard to get it fermenting properly again (plus, a fridge environment might have other food molds that could latch on). Instead, if you need to take a break between batches, store the SCOBY at room temp in a jar with enough kombucha tea to cover it (this is often called a SCOBY hotel). Every few weeks, add a little sweet tea to feed it so the SCOBY doesn’t “starve”. A well-fed SCOBY at room temperature can stay viable for a long time. Some people have SCOBY hotels on a countertop that they feed with a bit of sugar/tea monthly - essentially maintaining a back-up culture.

Prevent Explosions

When you bottle kombucha for secondary fermentation (to carbonate it), be mindful of pressure. Kombucha can build up a lot of carbon dioxide if left at room temperature in a sealed bottle, especially if extra sugar or fruit was added. After a couple days of carbonation, move the bottles to refrigeration. Cold temperatures will slow the fermentation so the pressure doesn’t continue increasing. Exploding bottles are thankfully uncommon if you use proper bottles (thick glass meant for fermentation) and don’t forget about them at room temp for too long. Nonetheless, always exercise caution - place fermenting bottles in a box or cupboard (to contain any mess if one did pop) and avoid cheap flimsy bottles. Swing-top brewing bottles or repurposed commercial kombucha bottles work well.

Taste and Adjust Future Batches

Every batch is a learning experience. If your first batch came out too sweet, it likely was under-fermented - next time, ferment a few days longer or use a bit less sugar. If it was too sour for your liking, ferment a shorter time or add a little more sugar in the initial brew (or dilute the finished kombucha with juice). Take notes on how long you fermented and the temperature, so you can tweak as needed. Remember that as your SCOBY gets stronger (or larger) over successive batches, fermentation might go faster. It’s okay to trim down an overly thick SCOBY - you can peel off the older layers and keep a medium thickness layer for brewing. The SCOBY doesn’t have to be massive; even a piece of it can ferment a new batch as long as you have plenty of strong starter liquid.

By following these tips, you’ll prevent most of the common pitfalls that new kombucha brewers face. Much like tending a sourdough starter, brewing kombucha becomes more intuitive over time. You’ll get to know what a healthy SCOBY and ferment looks and smells like (generally a clean, acidic, vinegar-y or cider-like smell). Trust your senses: if you ever see something truly suspect (like mold) or a rotten odor, err on the side of safety and discard the batch, clean everything, and start anew. But in a well-maintained system, such issues are rare. Kombucha brewing is a rewarding hobby that, with a bit of care, will continuously produce delicious results and maybe even give you an appreciation for the unseen microbial world at work.

Happy fermenting!

The Big Book of Kombucha: Brewing, Flavoring, and Enjoying the Health Benefits of Fermented Tea, Hannah Crum, Alex LaGory, Hachette UK, 2016, ISBN 9781612124353